Disclaimer: The contents of this blog are my own and do not represent the views or opinions of the Peace Corps or the United States Government.

First, a word on language. For such a small country, Malawi has a pretty diverse amount of languages. There are about 10 or 11 total if we don’t count Chitipa, Malawi’s northernmost district. Due to a variety of geographical and other factors, Chitipa alone has upwards of twenty languages. The main language used in Malawi is Chichewa, which is native to the Central Region (Malawi has 3 regions: Northern, Central, and Southern).

(Side note: The Chi- at the beginning of most words in Chichewa is a prefix meant to denote something big. Thus most languages in Malawi are denoted by placing a chi- in front of the name of that tribe. Thus Chichewa is the language of the Chewa people and Chitumbuka is the language of the Tumbuka people and so on).

Chichewa is taught in all primary and secondary schools throughout the country, so people living outside of the Central Region can generally understand it. In the Southern Region, it has overtaken some of the more localized languages like Chiyao, Chilomwe, and Chisena. Although these languages are still spoken, they are increasingly being spoken less and less as parents favor teaching and speaking to their children in Chichewa (in my experience, this is particularly true with Lomwe. I’ve yet to meet anyone under the age of 40 who could speak Chilomwe). In the Northern Region, Chitumbuka is the dominant language and it has yet to be overtaken by Chichewa. Although many people in the north are fluent in both English and Chichewa, they speak to each other and to their children in Chitumbuka for everyday interactions.

All that’s just in case you wanted some context! Now on to the fun stuff. Here are the most common things that I hear daily, weekly, or multiple times a day here in Malawi

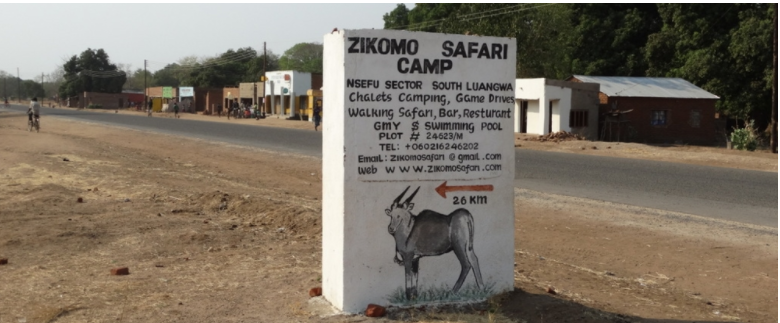

1. Zikomo

No post about Malawian language would be complete without this word which I use and hear used at least 20 times per day and usually more. Zikomo typically means thank you but you can pretty much use it whenever you have no idea what else to say. It can mean “excuse me” when passing someone it’s usually also used as “you’re welcome” in response to thanks, it can be used as a greeting, and many other things. There is a companion word, ndathokoza, which is present in many African languages, that simply means “I am grateful.” Whenever I receive a gift or buy anything, I usually say both of these words multiple times. To an outsider it might seem quite comical, since zikomo is also the response to zikomo. “Zikomo.” “Zikomo.” “Ndathokoza.” “Zikomo.” “Zikomo kwambiri” (thanks very much).

2. BOH?!?!?!?! (variously spelled “bo”)

I’ve written it like this because that’s usually how I hear it pronounced by very small children. This is a very informal greeting, typically accompanied by a thumbs up and a smile. It’s used amongst people who are the same age (usually younger people), but whenever children see a white person, they love to shout “azungu boh!!” It can also be said in repetition: “Boh boh?” and the response is “Boh.” Boh literally means good. You might ask someone “Ulendo unali bwanji?” (how was the journey?) and they might answer “Unali boh!” (It was lit, fam (N.B. not a literal translation)).

(Side note: I heard a rumor that this word actually comes from the Portuguese (the Portuguese and Britain had a dispute over parts of Malawi during colonization and eventually colonized Mozambique, Malawi’s next-door neighbor) “bom dia” meaning “good morning.” I have no idea if that’s true, but it makes for a nice story).

3. Iwe, choka!

This literally means “You, go away!” and is slightly rude if you’re saying it to a person your own age. It’s commonly used in talking to animals. In homestay, the goats used to try to come into our house while we were eating and my amayi would always angrily get up and yell “ah ah, choka iwe!” and begin chasing the goat all over the yard until it went away. Close friends also use this phrase with each other in joking around, kind of the same way you might imagine some men saying “shut up you old bastard” in jest.

(Sidenote: despite the fact that “iwe” literally means “you (informal),” it’s used much more frequently and differently than English. People commonly use “iwe” the same way we might use “hey!” in America, or the way people say “come on, man,” or “bro.” I hear iwe used more commonly by itself than in sentences. (Sidenote to the sidenote: there’s a Peace Corps slang here of referring to all children as “iwes,” since when you use the word iwe you’re usually talking to children. “You’re an iwe” is now a certified Peace Corps Malawi insult, even though it technically doesn’t make grammatical sense, but I still use it frequently)).

4. Basi.

The “i” at the end is frequently left off so the word usually sounds like “bas.” This word can be used in a variety of ways and tones depending on the context. If it’s said alone, it means “that’s enough.” I would say it every day in the host village when my amayi poured water over my hands to wash before eating. It’s frequently said before leaving somewhere: “Basi, ndapita.” (literally: “Enough, I have gone.”) You can use it if someone is annoying you: “Iwe, basi.” It can also sometimes be used to mean “only.” In training we were taught to tell people “I don’t get paid a salary, I just receive an allowance basi.” Another example: “I like all vegetables but with fruits I like bananas basi.” The words iwe and basi are frequently used by PCVs to sprinkle English sentences and we use them with each other when no Malawians are around. I have no idea how I’m going to remove them from my vocabulary when I return to the U.S.

5. Ndikubwera.

This literally means “I am coming,” but no one uses it like that. I almost always hear this phrase used (in both English and Chichewa) when someone is getting up to leave. At first I thought maybe people were just confused about the meaning of the word in English but once I heard that the same thing was said in Chichewa as well as how ubiquitous it is, I realized that there was a bit more going on. I eventually realized that people are using it to express the sentiment essentially that, “I am leaving now, but I will be back.” It doesn’t always mean that they will be back immediately, however. It may be several hours or even the next day. But they will return. I have now adapted to saying this in English to Malawians so much that it has become a habit and I forget that this is something I never would have said in America.

6. Tiwonana.

Both tiwonana and ndikubwera signify something deep about the culture here that, in my opinion, is vastly different from the U.S. Tiwonana is typically translated as goodbye, but it literally means “we will see each other.” Goodbye is too complete. Goodbyes can be final, but tiwonana and ndikubwera are never final. With those words, there is always the hope and perhaps even the expectation that you and the person you are chatting with will meet again at some point in the future. Some PCVs, upon leaving, say something like “It’s not goodbye, it’s tiwonana,” drawing out that subtle difference.

7. Lowani!

Literally, “Enter! (formal)” or “Come in!” but used much more frequently than in English (at least in my memory). In America, I feel that if I go to visit my friend, I should probably wait for an invitation or at least inform them of my coming. In Malawi, a guest is treasured. Sitting outside my house in the training village, if people were walking by, amayi would always come find me and say “Alendo afika!” (a visitor/traveler has arrived) and proudly have all of us come over and greet them. In Zomba, I used to visit one of my close friends at least once or twice a week, and he would always tell me “Lowani, lowani, tidye!” (come in, come in, let’s eat!). In general, here, people want to welcome you and practice hospitality with you.

(Side note: one of the common ways that Malawians translate this in English is: “Can you get in?” which I find simultaneously more and less direct than “lowani.”)

8. The Greetings

Alright my friends, buckle up. Greetings are hella important in Malawi and you’re about to learn ‘em all. The basic greeting for someone you haven’t met or someone you haven’t seen in a while (they’ve been away on a journey, perhaps) is as follows:

A: Muli bwanji? (How are you?)

B: Ndili bwino, kaya inu? (I’m fine, what about you?)

A: Ndili bwino, zikomo (I’m fine, thanks)

B: Zikomo (Thanks)

If there are multiple people in a room, you have to go around and greet all of them like that. None of this “How are all of you?” ish.

If you meet someone you know in the morning, you greet them like this:

A: Mwadzuka bwanji? (How have you woken up?)

B: Ndadzuka bwino, kaya inu? (I have woken up well, what about you?)

A: Ndadzuka bwino, zikomo (I have woken up well, thanks)

B Zikomo (Thanks)

If you meet someone in the afternoon or evening you greet them like this:

A: Mwaswera bwanji? (How have you spent the day?)

B: Ndaswera bwino, kaya inu? (I have spent the day well, how about you?)

A: Ndaswera bwino, zikomo (I have spent the day well, thanks)

B: Zikomo (Thanks)

Of course, in the real world people drop some words and add things, my favorite being that people drop “bwanji” and “bwino” meaning they’re literally greeting each other like this: “Have you woken up?” “I have woken up” “Thanks” “Thanks.” You can also add –nso to the end of bwino to add an also: “Ndaswera bwinonso” (I have also spent the day well).

I can’t stress enough how important greetings are here. People are shocked when I tell them that in America you can just walk by someone without acknowledging their presence (you can do that here as well, but really only in cities—when I’m biking somewhere I always say at least “zikomo” to anyone I pass). If I let my American side take over and try and get down to the business at hand without greeting a person, they may not tell me directly, but often they will wonder why I didn’t greet them. I usually notice a change in their tone and attitude towards me if I suddenly remember I didn’t greet them and then apologize and start over. Usually the greetings I’ve posted here are followed up with “What about your house? How is it?” and things like this. I realize that “How are you?” and “I’m fine” has become an essentially meaningless form of phatic communication in English, and it definitely is in Chichewa as well, but the fact that it is used so frequently gives it more meaning to me. The meaning is in the greeting itself and not in the words exchanged.

(Side note: as a teacher, we get to know how important greetings are the fun way. Our students are trained from primary school to stand up when the teacher turns around to face them. The teacher says, “Good morning, class.” The students respond, loudly and in unison, “GOOD MORNING, SIR/MADAM.” “How are you?” “WE ARE FINE AND HOW ARE YOU, SIR/MADAM?” “I am also fine, thank you.” “THANK YOU, SIR/MADAM. YOU ARE MOST WELCOME.” And then they sit).

9. Ndithu.

Literally, “indeed” or “that is true.” It can also just be used as conversation filler when there’s nothing else to say. In my own observations this latter use is more common in the Southern Region than the Central Region. It’s often said in a pair: “Mvula!” (rain) “Ndithu, ndithu (indeed, indeed). There’s a suffix which also means indeed in Chichewa: -di. Sometimes people add –di to ndithu itself for emphasis. “Kuli njala” (there is hunger). “Ndithudi, ndithudi” (very much indeed) or (you are very right).

(Side note: the “th” sound in Chichewa is not pronounced like the “th” in “thin.” Chichewa doesn’t have that sound. It’s pronounced like a normal “t.” “Why is that h there then?” you ask? The h is to indicate aspiration. In English a standalone t is already aspirated. This essentially means there is a breath of air behind the sound when you say it. Try saying the word “tart” and then say the word “start.” In English, “t” is aspirated unless it is immediately preceded by “s.” When you say “tart” you should hear the breath, but when you say “start” the breath should be totally absent. Chichewa has more of a distinction between these aspirated sounds, so the letters “k, t, and p” exist along with “kh, th, and ph.” (“Ph” is pronounced like a “p” rather than an “f.” The same principle applies as with “t.” Try saying “pot” and then “spot”). This can lead to a distinction in words that is barely discernible to native English-speakers. “Mpaka” (until) is pronounced differently than “mphaka” (cat), but despite hearing both of these words for seven months now, I still don’t hear the difference).

10. Ujeni.

My best translation of this word is “whatchamacallit.” In fact, I taught my form one class in Zomba the word “whatchamacallit” so that they would stop saying ujeni so much in class (I know it wasn’t a terribly useful thing to teach, but I wanted them to use English as much as possible!). Ujeni is used all the time to refer to literally everything: people, places, things, verbs, words you can’t remember. Basically, if you can’t remember what you were going to say next, just drop an ujeni in the sentence and the ujeni will finish the ujeni so that those other ujeni will know what the ujeni you are talking about. Ujeni. Some people use the word ujeni so much that it reminds me of the Rock Bottom episode of Spongebob. One of our friends in the north has a counterpart who is nicknamed “Mr. Ujeni” after how frequently he uses this word. I still remember my own counterpart in Zomba starting every argument he had to make off with something along the lines of “Let’s take an example of that ujeni…that uh who…that ujeni, that president of Zimbabwe Robert Mugabe…”

11. Azungu.

Technically this word just means “foreigner,” but it has come to specifically identify white or lighter-skinned foreigners. Although people still get called azungu regardless of their skin tone once people realize they are foreign. This is most often used by children screaming as I pass by on the road. Slightly older children will often follow it up with the phrase, “give me money!” (Many people like to respond to this request by saying “where is my money?” in Chichewa, which really confuses the kids, or saying something like “give me your pen!” back to the kids). Still, it is used by adults as well. In the market once, I was walking to a chippies (French Fries) stand with some friends and I heard the vendor’s friends yelling behind him in Chichewa “Make the price higher! They’re azungu!” Having just greeted him in Chichewa, he turned around and told his friends laughingly, “I can’t, they know Chichewa!” As annoying as this word can sometimes be (If people call me azungu repeatedly trying to get me to come to them I usually respond with “dzina langa si azungu” (my name isn’t azungu)), I understand that there are a variety of factors that go into its use. Children are often excited by the novelty of an outsider, and if I stick out more than anyone in a crowd, the term really does become useful to refer to me. Several times when I’ve been waiting for a minibus to fill up, the conductor has gone around trying to use me as an attraction to try to get more people to get on the bus (“Come on this bus, here’s an azungu who lives in a village! He knows Chichewa!” Etc.) Technically the word itself is “mzungu,” but in Chichewa, putting an “a” at the beginning of any word makes it respectful. So “azungu” can be termed a sign of respect if I look at it from a different perspective.

12. Pang’ono Pang’ono.

Literally: Little by little. It’s used to mean “slowly.” But people most often use it as a form of encouragement. When I was first struggling with how to make fires or how to wash my clothes by hand, my host parents would say “pang’ono pang’ono mudziwa” (little by little you will come to know how). When I was struggling with getting moved at site and settling here my new neighbor would tell me “pang’ono pang’ono.” (In English we might have said “one day at a time.”) The first proverb I ever learned in Chichewa was “Pang’ono pang’ono ndi mtolo,” meaning “a bundle of fire grows gradually (little by little)”—gradual and persistent attempts get the objective. (Side note: Essentially every language in Malawi has a version of this that sounds similar: Pang’ono pang’ono in Chichewa, pachoko pachoko in Chitumbuka, panandi panandi in Chiyao, Chilambia, and Chindali, kamana kamana in Chitonga, and so on)

Those are twelve of the most common Chichewa phrases I hear daily. But Malawians are also fun and creative with English as well. My all-time favorite example of this is something I’ve overheard twice now when two people were playfully arguing. One person sighed and, rather than call his opponent a liar, said “Ahhh, my friend, you are being economical with the truth.” Malawians also often refer to people they are pointing to as “this one” or “that one,” which can sound jarring to an American ear at first, but this is another thing I’ve gotten so used to now that I’m worried about how I’m going to get rid of it once I come home. (i.e. When I was introduced to the students at my new school, the other teachers would say “This one is your new teacher” instead of “He is your new teacher” or something like that). Other common English expressions you might hear are “Feel so free” and “You are most welcome.”