Disclaimer: The contents of this blog are my own and do not represent the views or opinions of the Peace Corps or the United States Government.

Girls. The answer is pretty simple. There’s this saying which exists elsewhere but I’ve heard it far more often in Malawi: if you educate a boy, you educate that boy. But if you educate a girl, you educate a nation. Which is true. You do. Unfortunately, in much of the developing world, this does not happen.

The literacy rate here is partial evidence of this:

Males: 70%

Females: 54%

There are a variety of obstacles standing in the way of girls’ education along with other things girls may not have the ability to do. These problems are unfortunately not unique to Malawi.

Chores are still divided among male and female here. Actually, I’m not even sure I should use the term “divided,” because this doesn’t match exactly what we think of when we think “traditional gender roles.” Typically when we hear that term we picture a man farming or working and his wife cooking, cleaning, and feeding the children. In Malawi, this is true, but the woman is also expected to work in the field. But the man is never expected to do any household chores. Although some people argue that in a traditional setup, the woman does more work than the man, in malawi that is empirically true. And many men refuse to do “ntchito za pa khomo” (domestic chores)

I went to visit my host family a few weeks ago. My host mother had been gone for a few weeks visiting her own mother in her home village. The house was a disaster. Everything was unswept (in a dusty place like Kasungu, this can be a major problem), there was trash everywhere, the chim wasn’t clean. My abambo apologized profusely. “Sorry that everything is so dirty,” he said. “Your mother isn’t here.” I asked him, “Are you not able to sweep?” He just laughed and changed the subject.

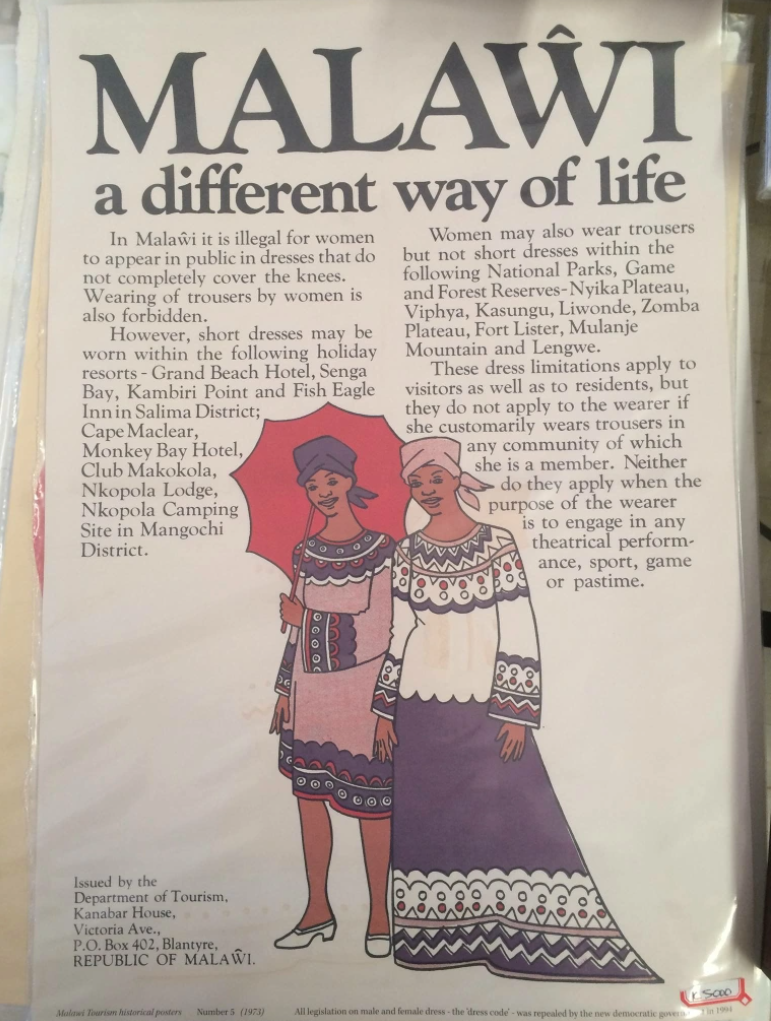

Under Kamuzu, women were prohibited from wearing trousers (pants). It was an extremely punishable offense. These days it’s no longer illegal, but the mentality behind it persists. Although women can comfortably wear pants in the cities, in rural areas a woman wearing pants is a large taboo. Many people, women and men, will think that a girl wearing pants is a prostitute. A few weeks ago, some girls at my school wore pants under miniskirts while playing netball. They were punished severely. When I was doing a pen pal exchange with my students, I mentioned that almost all girls in America wear trousers rather than skirts. Some girls were enamored. They said “I would love to live in America so that I could wear trousers.” Other girls said this was one of the things they didn’t like about America, and they wished girls there would wear trousers. One girl told me that girls wearing trousers was against the Bible. Surprisingly for me, the boys in the class had nothing to say on the issue.

One of the female teachers who sits next to me in the staff room was discussing how marriage in Malawi works and I mentioned that many people in America divide chores between each other when they get married, but it isn’t expected that the woman do one thing and the man do another. “Ah, America, what a wonderful place,” she said. “You will have to take me there when you go back.” We both laughed. None of the men in the staff room laughed.

In most Malawian schools, a girl who becomes pregnant is expelled from the school. For a long time, it was only girls who were expelled. Somewhat recently, the rule was amended to say that the boy responsible for impregnating her is also to be expelled. This latter part doesn’t often happen though, partially because it would be difficult to prove, and partially because many times girls are impregnated by older boys or men who are no longer in school. But I think it’s telling that I learned about the first part of this rule within my first month in the country, almost a year ago. I learned about the second part of the rule in December—because it is almost never executed.

And then there is the way that these things can lay heavy burdens down for girls in their attempts to succeed, moreso than boys. A girl is expected to do household chores everyday before school and in a place like this, these chores are very involved: drawing water, starting a fire, cooking, sweeping the yard, washing the dishes. If the borehole is far, this can be even more time-consuming. Boys are expected to work in the field, but they can also do this upon returning home. It may take a girl several hours to do all of her chores and then she has a several kilometer walk to school. By the time she gets there, she may be late and the teacher will refuse to let her into class because of tardiness. At my school, both boys and girls are late, but significantly more girls are late than boys. (For commuters. In terms of the boys and girls from the hostel, it’s actually about the same because, for the most part, they are made to do the same chores). Then she goes home and has to do the same things again and loses any time to study. Compound this with the lack of electricity and lighting in a household as well as the fact that she has to get up so early to do chores and you begin to see why she is slipping behind in school.

Many parents also promote the early marriage of their daughters, or if not early marriage, then the goal is marriage rather than education. She should find a good husband. Because of this, the parents see her learning how to do domestic chores as far more important than learning how to school-related activities, which she may never use in rearing a child or taking care of her husband.

Then there is the problem of menstruation. Most women in villages do not have access to any sort of feminine hygiene product, both because of financial and transport limitations. They are only available in towns and even then they are very expensive. Many women simply free bleed when their time of the month comes, and are hindered from doing many activities because of this—like school. In the past boys, who didn’t really understand what menstruation was themselves, would make fun of girls for being pregnant if they came to school on their period and bled through their clothing.

In my opinion, the mentality behind all of these things is decreasing with younger generations. The word “jenda” In Chichewa basically means “gender issues” or “gender equality.” The vast majority of people in Malawi are aware of jenda. And most people these days would say they support it. They may disagree on the extent to which it should be taken, or with how to bring change about it, but most people, at least in education circles, agree that girls are at a disadvantage when compared to boys and need to be given assistance. And students are aware of this.

Teachers are taught to call on boys and girls equally (girls tend to be more shy in group settings than boys, since traditionally the men are the ones who speak in public, not the women), and sometimes this attempt at gender equality is extremely obvious. I once heard a teacher say out loud in a class, after a boy raised his hand, “no, I need a girl.” The issue of gender is in many government-issued textbooks. Students these days, particularly boys, are aware of these issues in a way that generations before them were not.

When I first came to my school, I was being shown around by a male student from the hostel when I asked if they all cooked for themselves or if they had someone cook for them. He said they did have a cook at the school, but he reiterated to me several times that he knew how to cook and could do it if he wanted to. It was as if it was an embarrassment for a boy not to know how to cook. Like I said above, none of the boys mentioned anything one way or another about whether women should wear trousers. But I’ve heard plenty of older men give their opinion on the subject. Male students know that menstruation is an obstacle for female students.

And yet, resentment can sometimes build up. Girls are given many opportunities by NGOs that boys aren’t, simply because girls are already starting behind. But from many boys’ points of view, this is unfair. When all you see is an NGO coming to your school, pulling only the girls out for a neat activity, and never you, what else would you think? I think it’s similar to the controversy over affirmative action in America. There have even been stories of boys intentionally sabotaging girls’ education because of jealousy over this. And really, it makes sense, because the girls’ attitudes were never really the problem. To believe that you can enact social change by only working with the oppressed group and never working with the oppressing group is misguided at best. Not only that but doing things which make the oppressing group even more angry can potentially create even more problems.

This is why many development agencies, including Peace Corps (which did this earlier than many other agencies) have entirely changed the gender framework, to focus on issues that affect women and girls, but while being inclusive of all genders and focusing on addressing the mentalities and problems that boys face that might lead to them sowing gender divisions as an adult.

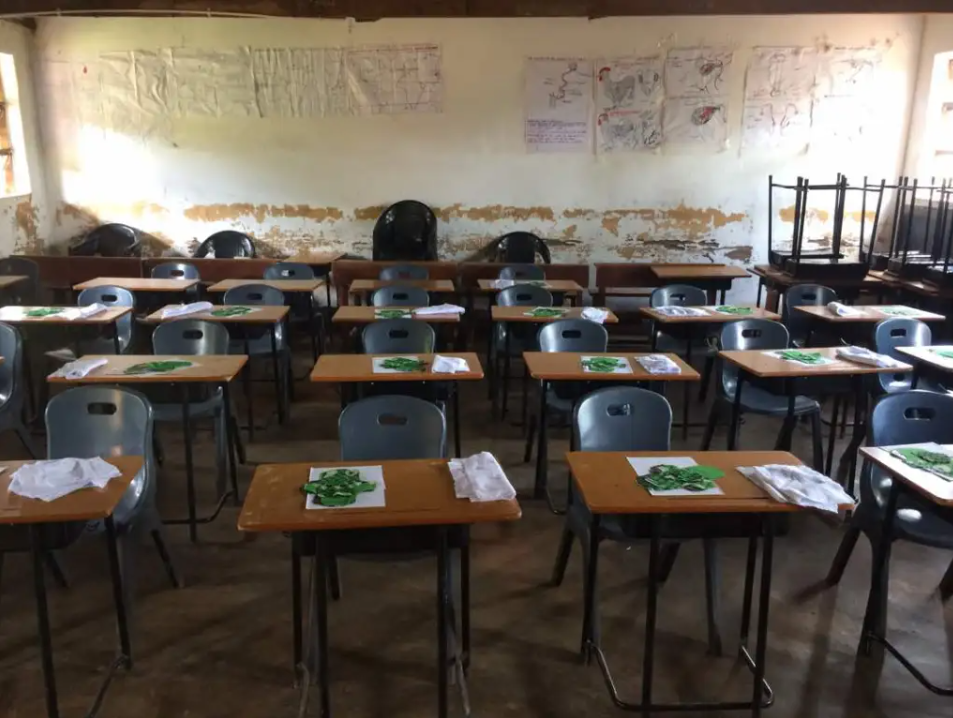

One thing I can do as a volunteer is called a Pad Project.

A pad project is an activity Peace Corps volunteers do wherein they, along with a member (or members) of the community, teach people how to make reusable menstrual pads out of chitenje (a local fabric easily found here). It was originally focused on adolescent girls, but we are beginning to try to branch out and do it with boys as well, and I just recently did one with adult women. While sewing, we discuss issues of HIV, female and male anatomy and facts and myths surrounding menstruation. Although girls often have a coming-of-age ceremony with older female relatives at the time of their first menstruation (Chinamwali—literally “the big grown-up woman”), sometimes they are not taught facts about menstruation or anatomy during this time which can lead to belief in harmful myths surrounding sex or HIV later on. My friend Val, a female volunteer, helped me out with these.

Our first pad project was at the school with 4 students from each Form, along with some students who had learned how to make a different type of reusable pad in another district, two mothers from the PTA and two teachers (one male and one female, my counterpart). The male teacher was ecstatic upon completing his pad and told me he was excited to give it as gift to his wife.

The second pad project was in my counterpart’s church. She had told several of the women there about our activity and they became interested as well. So we did one with half adult women and half teenage girls. This one was a bit difficult because we had to use Chichewa for almost all of it and all of the instructions are in English. My counterpart did a lot of translating. When it came to body parts, we used English because it’s taboo to mention any private body part in Chichewa, even if it’s the actual name of the thing. People are much more comfortable discussing sex in English than they are in Chichewa.