Disclaimer: The contents of this blog are my own and do not represent the views or opinions of the Peace Corps or the United States Government.

English is the language of a people who have probably earned their reputation for perfidy and hypocrisy because their language itself is so flexible, so often lightheaded with statements which appear to mean one thing one year and quite a different thing the next

–Paul Scott

I don’t know what’s more difficult, life or the English language.

–Jonathan Ames

Americans who travel abroad for the first time are often shocked to discover that despite all the progress that has been made in the past 30 years, many foreign people still speak in foreign languages.

–Dave Barry

The language I have learnt these forty years,

My native English, now I must forgo;

And now my tongue’s use is to me no more

Than an unstringed viol or a harp,

Or like a cunning instrument cased up

Or, being open, put into his hands

That knows no touch to tune the harmony

–William Shakespeare, Richard II, Act 1, Scene 3

O nation miserable!

With an untitled tyrant bloody-sceptered

When shalt thou see thy wholesome days again?

Since that the truest issue of thy throne

By his own interdiction stands accursed

And does blaspheme his breed…

Fare thee well!

These evils thou repeat’st upon thyself

Have banished me from Scotland

O my breast, thy hope ends here.

–William Shakespeare, Macbeth, Act 4

“Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow creeps in this petty place from day to day.” These lines, from Act V of Macbeth, have been on my mind a lot lately. The Form 4s (seniors) have to read Macbeth, before being tested on it on the MSCE, the final exam they take to get the equivalent of a high school diploma.

I should mention at the outset that at first this seemed absurd to me, as it does to many volunteers, and there are certain aspects of it which still baffle me. American high school students, whose first language is English, often have no idea what Shakespeare is saying. And these are students who have access to immense resources. No Fear Shakespeare, free Shakespeare interpretations and analyses online, even the simplicity of every student having a book, a book which they can take home—these are all things that the vast majority of high school students here do not have access to. By the time they reach Form 4 (12th grade), many students are already far behind where they should be in reading, so asking them to understand Shakespeare seems exceptionally untenable. I once told a Form 4 student that he shouldn’t feel inadequate for struggling with Shakespeare since even native speakers struggle with it. “If they struggle, then how much more we do, Madam” was his response.

Yet, they read it. And many are successful and understand it, I’d even argue often better than American students. For one thing, the subject matter is just so much more relevant in this context. Macbeth is all about the temptation towards taking power when it’s not deserved and life under an unstable regime, both things that are quite relatable in an African setting, even if there have been changes in Malawi in particular in recent years. Plus, there are witches and prophecy, things that we have to suspend disbelief or reach back far in our history to understand in the States, but not in rural Malawian villages. Ufiti (witchcraft) is something that is very real here and now, in the present.

But it isn’t just the story. There’s a determination to learn here that I have seldom seen paralleled elsewhere. Most students study constantly and many frequently ask me for help. One of the most surprising things when I first came here was the vocabulary of English speakers. Most English speakers know basic vocabulary and extremely complex vocabulary but lack the middle ground intermediate vocabulary or grammar, which often leads to very bizarre situations, such as the one where the same student who once was able to describe the job responsibilities of an actuary, the next day was unable to give me the definition of the word “citizen.” Or another student, who wrote an eloquent rebuke of polygamy using very large words which typically made sense, but so riddled with grammatical mistakes, that it was often difficult to understand the overarching argument.

There’s a very common phrase here that I hear among (particularly more educated) people whenever they discover they’ve made a mistake when speaking English: “English never loved us.” It’s said with sarcastic derision towards themselves, regardless of the fact that their English is nearly perfect. Yet when we speak Chichewa that is riddled with hundreds of errors in every sentence, people express their amazement. When people compliment my Chichewa or ridicule their own English, I occasionally want to scream. A near perfect English speaker here might speak better English than me, but make one spelling mistake or one very minor grammatical mistake and become very embarrassed and tell me, “English never loved us,” but go on to tell me my Chichewa is good, as if their English isn’t perfect. I am nowhere near a native speaker of Chichewa, but a significant portion of Malawi has a native level of English and nearly all citizens at least know basic English words and phrases. People are amazed when we know simple words and greetings in Chichewa, but become embarrassed when they slightly mispronounce a word like “anachronistic,” which a lot of native speakers don’t even know.

Isn’t it strange that we expect the rest of the world to know English to the level of a native? It may be difficult to conceptualize for many monolingual Americans, especially those who constantly complain, “if you’re going to come to this country, learn English!” It takes a long time to reach an intermediate level in English and years to reach anything close to a native level in English, especially the later someone begins learning.

I’ve thought a lot during the time I have been here about why I even teach English. The simple answer—it’s the international language of the day, just like French was before that, Latin before it, and Greek before it. But that answer doesn’t tell the whole story. Why am I here in Malawi teaching English? Why is English the international language anyway? And the simple answer to that question is imperialism. This is a former colony. Some people in the northern hemisphere got together, decided their culture and language were better than the culture and language that already existed in this place, and forced them to start learning it. Don’t get me wrong; I have no qualms about teaching English now, because in the world we live in now, this is the reality. It is indeed the international language, and in the Malawi that has been created post-colony and in the post-colonial world at large, it is very difficult to succeed (according to the way people define success here) without having at least a proficient command of the English language.

But a lot of people don’t. In town, I meet people who speak better English than native speakers, but many of my students are far behind the level they should be at. And another small minority are ahead. My test scores range from 6% to 90%. And those are not outliers. Every possible score imaginable lies in between. In one class of 72 students (over twice the size of what we would consider a reasonable class size in America—some of my friends teach classes of over 100), every student occupies a different range of skills and knowledge, and due to the class size and the way the education system is structured here, it’s nearly impossible to work with all of them individually, which would be ideal. In addition, traditionally Malawian teaching is done by lecturing only, simply writing things from a book on the board and expecting students to memorize and understand it on an exam. This is changing these days, but the process is extremely slow, and many older teachers still stick to the traditional style. Because of this, many Education volunteers here, when we attempt to teach in a more American way, encounter problems wherein students (not knowing what the correct answer is) will simply copy a long passage directly from a book or the question, hoping they’ll get partial credit for it or that the answer is in there somewhere. And one shouldn’t blame for this, since it’s how they’ve been conditioned since standard one (first grade).

But it also wouldn’t be appropriate to blame the teachers in this way, since in many of the types of schools Peace Corps Volunteers are placed, only one book is available to teach those 72 students. So the only way to adequately distribute the information is to copy it on the board. This might not be the case if there weren’t so much to teach, but there’s so much to fit in a single year that teacher can’t stop and check to see if each student understands what’s been taught, lest they fail to finish the curriculum. The obvious solution to this is for the government to provide money to purchase textbooks, which is essentially a pipe dream, since not only is Malawi one of the poorest countries in the world, in which the majority of the government’s money comes from foreign donors, it also suffers from rampant corruption, as well as a budget in which education receives a lower percentage of funds than many other interests (yet still higher than the percentage it receives in the United States, the last time I checked).

All this seems depressing when one first encounters the facts of the situation, and these facts did depress me before I came here and right after arriving. Occasionally, it still does, but not often. Soon after arriving at my school, I began to see how people work to overcome these challenges and learn to do so in much more creative ways than we ever would dream of or need to in America.

In December, I asked the Form 4s if they had any interest in attempting to stage Macbeth and actually perform it. Literary culture is not very big here, but oral storytelling is, and I thought they might understand the play and get more involved in it if they saw it live and if their friends took part of it. Through the same grant I used to get the school a large amount of Chichewa-English dictionaries, I also had gotten photocopies of Macbeth with the original text and a modern paraphrase side-by-side. Each of the Form 4s had a copy, so lack of books was no longer an issue, and because of the dictionaries and the paraphrased text, they could now understand the plot more easily. However, they were still nervous because of the difficulty and age of the English. Not to mention, none of them had ever performed in any kind of play before, let alone in English, let alone Shakespeare. My first suggestion of the idea was met with a resounding “uhhhhhhhhhhh” and a collection of dazed or horrified faces in the Form 4 classroom.

However, several students did not have that expression. Some seemed excited by the idea and wanted a challenge. So, over the next few days I worked with my Head of Department, who was the one actually teaching English in Form 4, to create a list of all the characters we needed. We arranged them in order of the amount of lines a character had. That way, students who were confident and willing to take up the challenge would sign up for the more difficult and bigger roles, while those who may have felt less confident in their skills could still take part, but not feel pressured or in over their heads. My hope was that by taking part, even those who had minor roles would have confidence instilled in them and the knowledge that they could do things like this; it wasn’t out of reach for them.

But not everyone in Form 4 signed up. So we went to Form 3 (11th grade). We found a few willing participants there. But then, we still didn’t have enough, so we found some students from Form 2, the class I teach, who were willing to participate. Both I and my Head of Department agreed that Form 1s didn’t yet have enough experience to tackle the play, and they would likely benefit more from watching their friends perform.

In the end, we had 31 students total who took part in the play. We practiced from January to the end of May (with some significant breaks in between). We practiced twice a week, when it was possible—time is conceptually different here, so sometimes people arrived so late that it effectively nullified the practice, or an extended school break or excessive absences made it impossible. We interspersed a few Saturday practices here and there. But most of the students came to every practice. And they all memorized their lines. They were extremely dedicated. The student playing Malcom caught malaria two weeks before we were to perform the play and didn’t bring his script with him when he went home to recover. When he came back, he stayed up late one night memorizing the lines he hadn’t gotten yet and summarizing others which it would have been impossible to learn in such a short amount of time.

In order to make the play more relatable to the students (and the Malawian audience we wanted to come and watch the play), we changed the setting from Scotland to Malawi. This manifested itself in several ways. The most prominent was that we changed the role of the king to that of a local chief. Our chief lent us his formal robe for use in the play, which was extremely kind, gave an extra air of authenticity to the play, and enabled the audience to instantly recognize who the actor was supposed to represent. In the original play (and in Europe in those days), trumpets would play whenever the king entered. In Malawi, there is a specific type of clap that people do whenever a chief enters. Throughout the play, whenever the chief entered or left the room, the audience would clap in that way.

Another change was the witches. Since Malawi still has witchcraft as an aspect of its culture, it was somewhat easy to adapt this. We simply had to change the appearance of the witches to match the perception here than in Europe (pointy hats, warts, long noses, hunchback, etc.) Here, witches have white and black on their faces and arms. Before the play, the students playing witches rubbed ash and charcoal on their arms and faces to make them grey, black, and white. In this way, everyone knew that they were supposed to be witches.

A third change was changing English to South Africa. In the original play, Malcom flees to England after the murder of his father and Donalbain to Ireland. At the end, Malcom leads the English army against Macbeth in Scotland. Since we had changed the setting to Malawi, we changed Ireland to Zambia and England to South Africa. At the end of the play, some soldiers carry a (homemade) South African flag across the stage, representing that they are South African soldiers, coming to Malawi to rescue people from the chief. Because our school’s neighbor is a Malawian military battalion, they lent us uniforms for the soldiers in the play.

When I and other teachers first discussed this idea, I thought that it was original. Of course, I knew Shakespeare had been adapted to other eras and places (who could forget Leonardo DiCaprio’s Romeo carrying a gun, yet still speaking Elizabethan English?). But I hadn’t thought it had been adapted to something akin to an African setting. I was wrong.

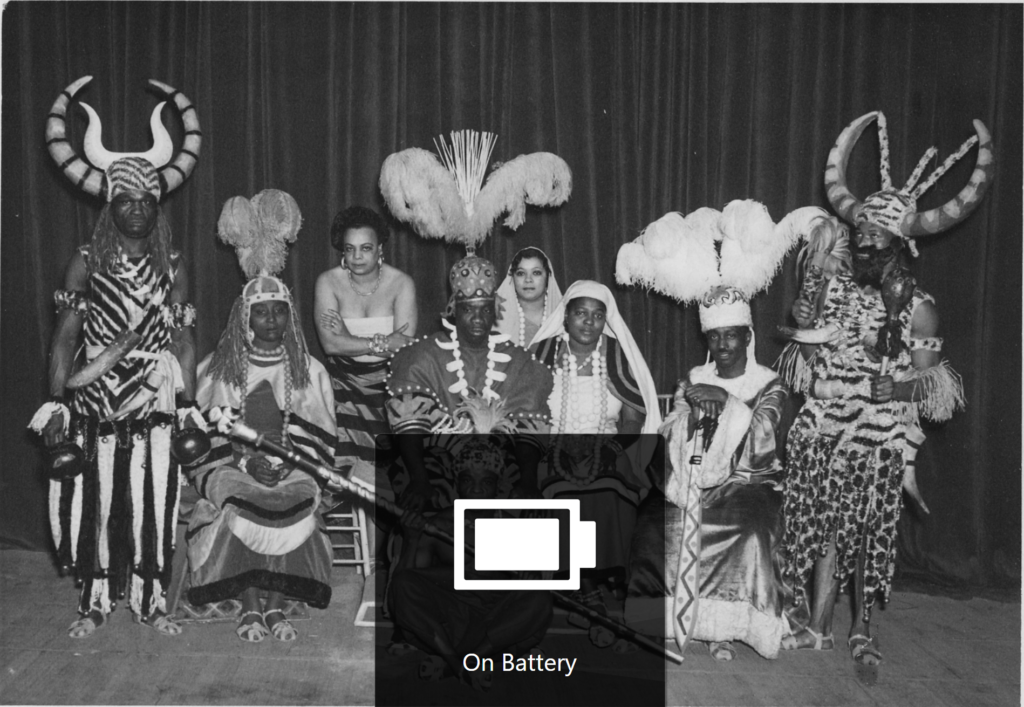

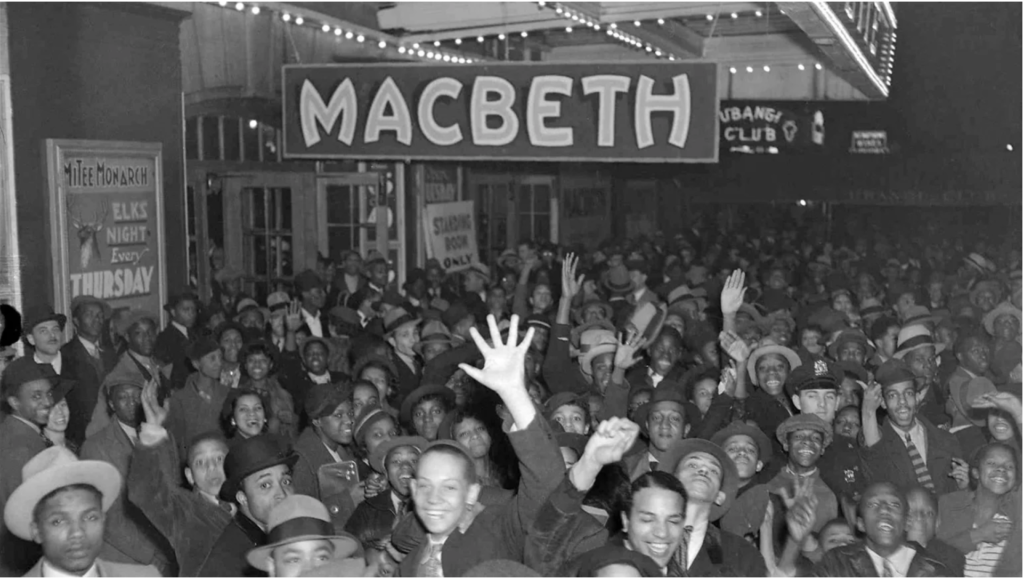

In 1936, Orson Welles, then barely in his 20s, directed a production of Macbeth in Harlem with an all-black cast, which in time came to be known as ‘Voodoo Macbeth.’ Welles changed the setting to a Caribbean island similar to Haiti and replaced the witchcraft in the play with Haitian voodoo. He hired actual witch-doctors to help with the play. He did this as part of the Federal Theatre Project, under the WPA at the time, in order to give black actors the opportunity to play actual roles instead of racial stereotypes common at the time.

Because of that standard at the time, many black intellectuals and actors at the time protested the production, assuming that Welles was simply attempting to mock his cast the same way other productions at the time had. At the same time, whites and Shakespeare purists complained that Welles was ruining Shakespeare by changing the locale and not using any white actors. After it was released, it received widespread acclaim.

“By all odds my great success in my life was that play,” he later said in an interview. “The opening night there were five blocks in which all traffic was stopped. You couldn’t get near the theatre in Harlem. Everybody who was anybody in the black or white world was there. And when the play ended there were so many curtain calls that finally they left the curtain open, and the audience came up on the stage to congratulate the actors. And that was magical.”

Even today, Hollywood still seems to struggle with the issues surrounding this play, and Welles attempted this over 30 years before the process of desegregation even began. The last few minutes of the play are available on YouTube. I have no doubt that the high quality of acting is in large part, what caused the acclaim and launched several actors’ careers after it ended. But I also think it would be wrong to discount the role that changing the setting to one that might be more relevant and relatable to a modern audience (and one closer to home), in large part created the hype and helped people become more invested in the production.

When we were practicing this play, I saw students be creative in a way I had never seen before. Critical thinking is something that most students struggle with here (many are simply too used to rote learning), and often don’t know how to begin learning or practicing it. The play helped them with this, and I think the reason for that was because the setting was here, in this place they are familiar with intimately. Most of the changes we made to make things more ‘Malawian’ rather than ‘European’ were ideas that came from the students, not me or other teachers. By the time they performed the play in front of an audience, they had worked on solving problems like these enough times that whenever a mistake was made, the students would come up with a solution on the spot much quicker than I could, something that I don’t believe would have been possible 6 months before.

Of course, the play was far from perfect. People stumbled over their lines, forgot lines, walked off the stage at the wrong time, spoke too quickly, switched two similar scenes, and most people were difficult to understand because they didn’t enunciate clearly (the education system here implicitly prioritizes writing over speaking, so many students struggle with pronunciation in general, and Shakespeare just adds an extra layer of complexity to that). However, they were able to get through all of that without any issues because of quick, on-the-spot thinking, mostly by them and their friends. Also, in between acts, we had someone read summaries of what was happening in Chichewa, so that the community (most of whom don’t speak English) would be able to understand what was happening. This helped aid the enunciation issue.

However, the main reason for them doing the play is because they will be tested on it on the MSCE, the final exit exam at the end of secondary school. And I’m fairly confident that all those who participated will be able to get a hundred percent. And that is because they know the material, regardless of how well the play was, or how great the acting was. And as an added bonus, the form 2s and 3s, who haven’t even read Macbeth yet, will have a headstart when they get to Form 4.

A video of the performance was taken (thank you to everyone who came and visited from Lilongwe! Your presence really did mean the world to me and the students). Eventually, I will be able to put that video on a flash drive and give it to the teachers at my school, so that in the future they can show it to their students and say, ‘See? Your friends, who were no different from you, did this. It is possible.’ My hope is that by seeing that video, and seeing what their friends achieved that they will never even have to start believing the phrase ‘English never loved us,’ because they’ll know that even difficult things like these are possible with practice. And that the only way to improve on past mistakes is to keep making mistakes and move on.

Six months ago, when I first asked the Form 4s if they would be willing to do this, I never would have dreamed that they’d get as involved and invested in it as they did. They taught themselves far more than I did, and learned by trial and error much more than English or Shakespeare. They learned to problem solve and they increased their confidence, which in my estimation, is worth far more than knowing a few words from the English of 400 years ago. This is one of my final projects, and I’d say it’s tied for the highlight of my service with the reading buddies program from last year. It has definitely been, by far, the most interesting (and longest).

As my service here draws to a close and I continue to think about the moral complexity of being here, in a former colony, as a Westerner, in order to teach critical thinking, I consider how much the students taught themselves. I am comforted by a quote from William Kamkwamba’s book The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind (which is now a movie on Netflix). He describes a moment in which he and his childhood friend Geoffrey were messing with old discarded mechanical instruments from a junkyard, trying to rig a bicycle up to power a radio:

“’Geoffrey, my experiment shows that the dynamo and the bulb are both working properly,’ I said. ‘So why won’t the radio play?’

‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘Try connecting them here.’

He was pointing toward a socket on the radio labeled AC and when I shoved the wires inside, the radio came to life. We shouted with excitement. As I pedaled the bicycle, I could hear the great Billy Kaunda playing his happy music on Radio Two, and that made Geoffrey start to dance.

‘Keep pedaling,’ he said. ‘That’s it, just keep pedaling.’

‘Hey, I want to dance too.’

‘You’ll have to wait your turn.’

Without realizing it, I’d just discovered the difference between alternating and direct current. Of course, I wouldn’t know what this meant until much later.

After a few minutes of pedaling this upside-down bike by hand, my arm grew tired and the radio slowly died. So I began thinking, ‘What can do the pedaling for us so Geoffrey and I can dance?’”