Note: The views expressed in this blog do not represent the United States Peace Corps or the US government in any way.

Not long after arriving at the homestay village, one of our sessions was on the history of Malawi. I really like history and I think knowing the history of a place really contributes to understanding its current issues and culture. Malawian history is hard to find, especially history told by Malawians themselves rather than Westerners. I thought for this post, I would just copy my notes directly from that session, so that you all can learn a brief lesson on Malawian history alongside me, in order to understand the context of all the things that you might read about me doing later on a bit better. The first paragraph is a lot of delineations of tribes so feel free to skip it if it gets boring or confusing for you.

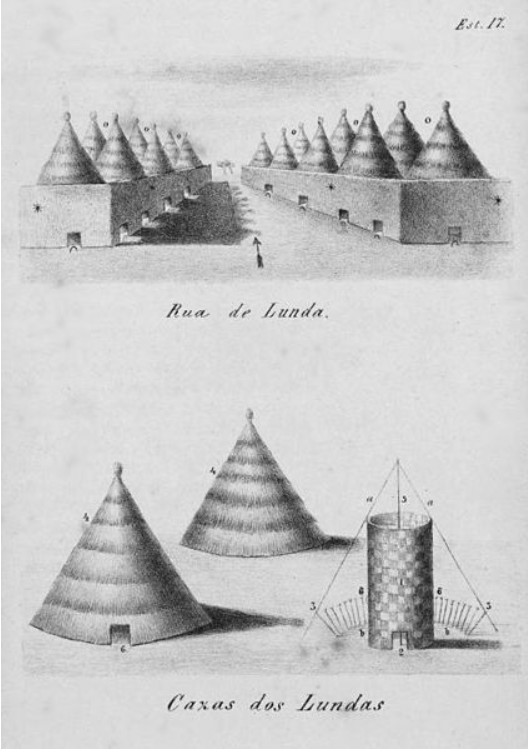

The Bantu were the original inhabitants of Malawi. They were very short people. The Chewa people (also called Mang’anja people, although these are considered different groups today) came from Congo around the 13th-14th century CE along the Zambezi River. The Chewa founded the Maravi Kingdom (where the name Malawi would eventually derive). The Tumbuka came not much later and founded Karonga Kingdom in what is today Northern Malawi. Then the Ngoni came from South Africa. The Ngoni were warriors. The settled in the Central Region but many moved north. The Ngoni enslaved many Chewa. They eventually settled in Mzimba in 1856. Around this time, the Yao moved to Malawi from Mozambique, bringing himself with them.

The Yao took a lot of land in southeastern Malawi. The Yao already had a good business relationship with Arabs, from whom they bought guns. They often worked with Arabs to enslave members of other tribes with their weapons. Yao today are largely Muslim due to their interactions with Arabs. Most of the Yao converted to Islam around 1840. And today other tribes often do not trust the Yao due to their past connection with the slave trade.

Later, the Lomwe came without fighting and in smaller groups. They also integrated very easily into other tribes, and as a result, they have nearly lost their language. Only old Lomwe people speak Chilomwe these days. The Tonga are the descendants of the Chewa, but they moved up north and stayed there. They had a war with the Ngoni warriors who were already there. The Sena are a hybrid of Chewa/Mang’anja and the tribes of Mozambique. People in these days ate mostly sorghum and millet. When the Portuguese came in 1600, they brought maize; which eventually replaced these. Today, Malawi’s main dish, nsima, eaten with almost every meal, is corn-based.

The first Christian missionary came in 1857, first attempting to work with the Yao but finding it difficult to convert them. Since the Yao already knew of Jesus from Islam, they weren’t very impressed by Christianity since they didn’t consider it anything new. The missionaries moved to Mangochi, where they converted many of the Chewa slaves of the Yao. They then moved north where the Tonga were at war with the Ngoni. The Christians began providing guns to the Tonga for their protection( so the Tonga had no choice but to convert to Christianity in order to keep their physical protection. (My own words, not in my notes: they were basically bribed into Christianity). This same thing happened to the Tumbuka. This is why the Tonga and Tumbuka people have the highest literacy rates in Malawi. Christians emphasized education and literacy. Colonizers came to Africa for 3 reasons, what we call the 3 C’s: Civilization, Commerce, and Christianity. The Yao struggled with literacy but excelled in math and commerce. Even today, the Yao are mostly traders.

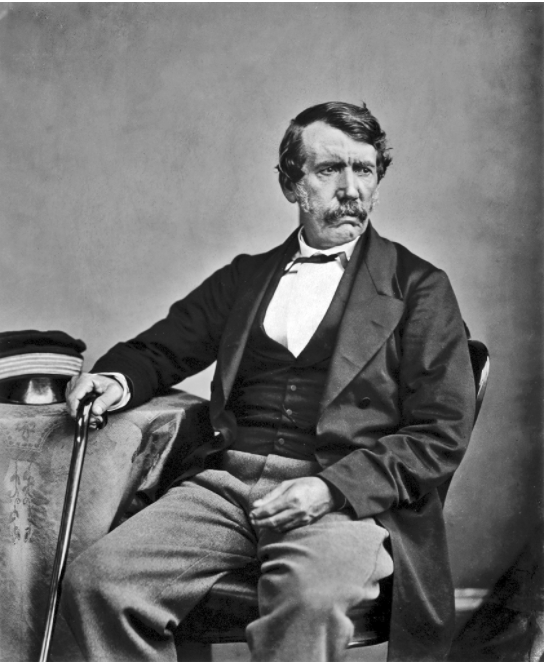

David Livingstone, upon encountering the Yao, went back to Britain and gave speeches, so many people came to Malawi and founded educational centers and schools. Most people prior to this learned by storytelling. People here were expert storytellers. There was a rule that you could not go to school unless you converted. The mission education system eventually fell apart because local teachers were untrained and there was no norm. By 1907, each post had a teacher training facility. By the 1920s, an American organization did a study on education in Malawi. One conclusion drawn was “bring more women into school.” They also discovered a need for structure, but many school-churches refused to be involved with the political leadership because the influence of religion was so obvious. The first Ministry of Education was in 1926. It is important to emphasize how important education was to Malawians. Some Malawians tried to resist the colonial authorities in the 1940s, but they felt incapable due to the lack of education they had. That’s why Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda was called back–but more on him in a moment.

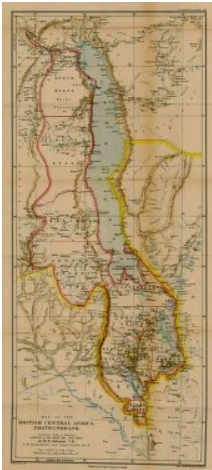

About the lake: Lake Nyasa–Malawi basically means “flames” and it was called this because the lake appeared to be on fire sometimes (The Malawi national team today is called the “Flames.”). Nyasa is the Chiyao word for lake [I’ve already discussed in a past post how David Livingstone misnamed the lake “Lake Lake” so I won’t go into that again] but nyasa means lake and during the colonial period, Malawi was called Nyasaland, land of the lake. Malawi is about 20% lake and because the country is so skinny, the lake is a pretty significant part of life here. Many people who were not immune to malaria or other water-borne diseases would move north to be cooler, bringing some of those diseases with them.

In 1895, the British created their own map of Malawi with their own borders. Malawi became Nyasaland around 1907, as a British protectorate. In 1957, it became The Federation of Northern and Southern Rhodesia and Nyasaland (today these are the countries Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Malawi). The federation ended in 1963. It got its independence on ) July, 1964 and was called Malawi.

The main reason for British colonization was to protect Malawi and other already-existing British colonies from possible encroachment by the Germans who had colonized Tangyanika (present-day Tanzania) to the north. The British didn’t really want to colonize or even occupy Malawi, but David Livingstone convinced them that it was a good idea on the pretense of ending slavery. He attempted to stop the spread of Swahili slavery from Karonga in the North, but had a difficult time doing so.

The word Boma, which is today a Chichewa word meaning “government, District, city, etc” was originally an acronym made by the British during colonization: BOMA–British Overseas Military Administration

In WWI, many Malawian soldiers were conscripted to fight both in Europe and in Africa (especially since German Tangyanika was so close). In fact, the first government in the original capital city of Zomba in the South, was primarily created to conscript people. John Chilembwe was a pastor educated in America who was very unhappy with the conscription of Malawians, and he led what is now known as the “Chilembwe Uprising” against the government.

Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda, the Life-President of Malawi, was called back to Malawi in the 1950s because he was a Britain and American educated doctor. In Malawi, education is a must for anyone in politics. Some people have been kicked out of parliament for it being discovered that they aren’t educated. Kamuzu ruled from 1964-1994. He controlled a lot of the private enterprises.

Kamuzu had what he called his “four cornerstones.” These were: Discipline, Unity, Obedience, Loyalty. This was pounded into the heads of Malawians (at this point I remember a Malawian saying “We were absolutely drilled with this.”) The thing all these words have in common is to be passive and accepting. This is why the US ambassador told us on the day she met us that her biggest frustration is that Malawians aren’t angry enough. They were fed this “don’t complain about anything” mentality for 30 years. Kamuzu wasn’t elected life president, but in 1971, a member of parliament suggested that he become life president, which he did (or attempted to anyway). Another important thing Kamuzu did was that in 1968, he introduced Chichewa into the primary schools, which united many of the tribes. He made Chichewa the national language. In 1992, democracy became more popular as the Cold War ended. In 1994, there was an election and Kamuzu lost.

Free Primary Education for All was introduced in 1994 (Secondary School–what we call high school–still Costs money), but it was poorly planned and created a lot of demands. There still weren’t and aren’t enough teachers (largely due to the HIV crisis–about 1 million people in Malawi live with HIV). Even though school is technically free, students and families of students still must buy uniforms and books.

A famine happened under Bakili Muluzi, the president who succeeded Kamuzu, partially due to a drought, but also due to a mismanagement of funds. The government was supposed to keep a large supply of share crops in case a famine occurred but on the advice of the World Bank and in order to pay off debt, they sold a large portion of it to other countries. When the famine came, there wasn’t enough food stored to go around. Malawians refer to this famine as “Kutupa,” which means “The Swelling” because many people could be seen outside with their skin bloated in the heat.

Bingu wa Mutharika succeeded Muluzi. He wanted his brother to succeed him as president (at this time his brother Peter was involved in a scandal and so was not very popular with the people), but he died in office, so in the early 2010s, his Vice President Joyce Banda, became president. She was not in power for very long. The government scandal now known as “Cashgate” happened under Joyce Banda. Cashgate refers to the discovery that the government was stealing large portions of international donor aid money that was meant to be distributed to the people. As a result, donors stopped budgeting through the government and began giving money directly to NGOs or organizations. From the outside it seemed like the amount of money Malawi was receiving had substantially decreased which made a lot of people very angry and they blamed Joyce Banda. In 2014, Banda was elected out of office, and Peter Mutharika (Bingu wa Mutharika’s brother) was elected president. He is the current president of Malawi.

2 footnotes:

I. some of the most common surnames in Malawi are Banda and Phiri. These are Chewa names, the former traditionally understood to be religious leaders and the latter traditionally understood to be political leaders.

II. A map of traditional leadership structure here in Malawi (or “How Chiefs Work 101 for Dummies”). Starting with highest power and proceeding to lowest. Chewa King (this exists only in Zambia not Malawi)–>Paramount Chief (There is one in Malawi)–>Traditional Authority or T/A (Sometimes there is a Senior and Younger T/A)–>Group Village Headman or GVH–>Village Headman–>Village–>Families

I hope this has been helpful and interesting at least a little bit for your understanding. Comment if you have questions or discussion points. I have a book on the history of Malawi which I hope to finish soon, so maybe I’ll eventually be able to answer it. If nothing else we can at least discuss these things!