Disclaimer: the contents of this blog are entirely my own and do not represent the United States Government or the US Peace Corps in anyway.

In less than 24 hours, I will be in Philadelphia, and a few days later, Malawi.

The biggest question from everyone has been this: When did you decide to do this?

I honestly don’t remember.

I can’t remember not deciding or not wanting to do this. In high school I had some vague idea of what the Peace Corps was (as I think most people do. I can’t count the number of times that people here have assumed it was some sort of missions organization and it sounded cool. Some friends and I were curious about what it actually was, so in 12th grade we were in a class that had computer screens and we weren’t doing anything (who does anything in 12th grade?). We looked up what it was and how to apply online. I liked the idea for some inexplicable reason that I can’t verbalize, but I did notice that at the bottom it said that almost every Peace Corps Volunteer has a college degree and this will make you much more likely to be accepted. “Alright,” I thought. “Go to college. Get a degree. Do Peace Corps. Sounds simple.”

That’s basically what I did, although I didn’t go right after college. I think my initial fascination with it was largely due to minimalism, which was already active in high school. Not having many things seemed appealing. And TBH I completely forgot about the Peace Corps until I ran into a volunteer in China years later.

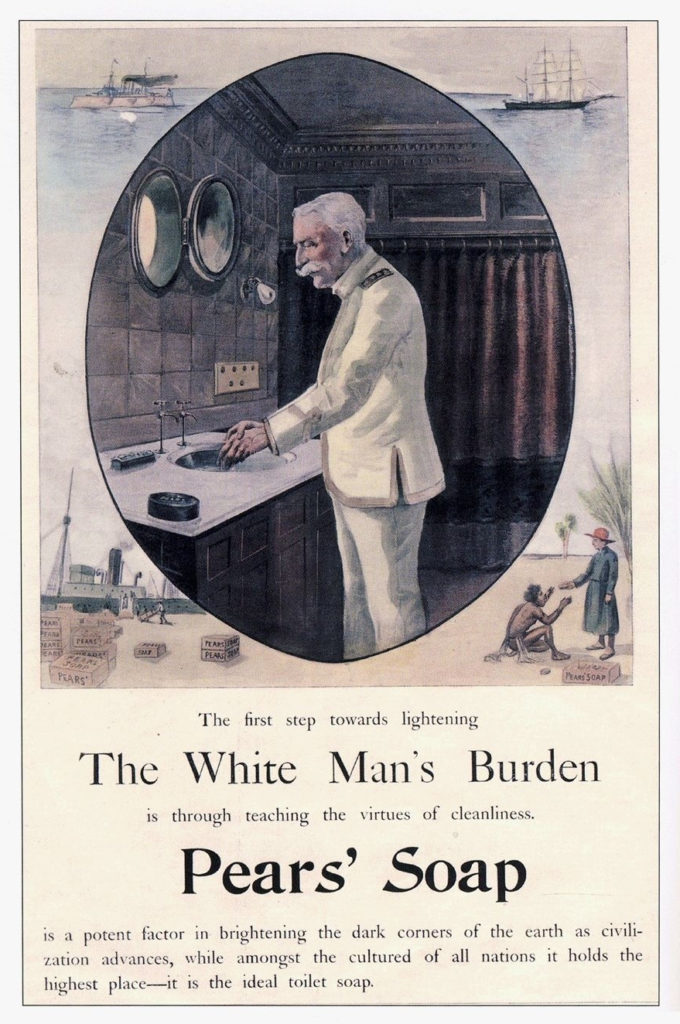

College only served to increase the minimalism aspect of the desire, but it also attached the desire to be helpful and the cynicism that comes with the knowledge that well-meaning helpfulness can go awry. Have you ever seen this picture?

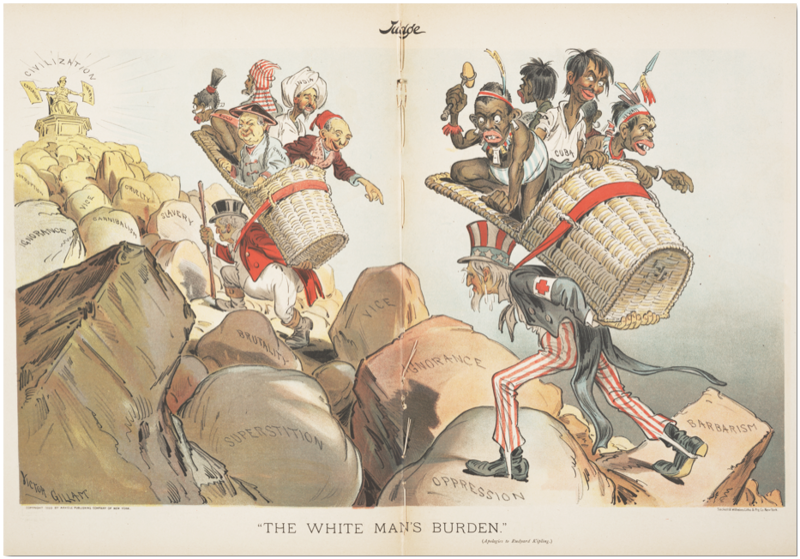

Or this one?

I remember the first time I saw them in high school. I thought I understood them then, but to be honest all I understood was that I was supposed to think they symbolized something bad. I wasn’t really sure why. It was only in college, when I encountered development (as well as missions), that I understood the issues with the photos above. Which is strange, actually, because it is only through the lens of the present that I was able to understand the past, when really, it should be the other way. To me, this is evidence that we actually haven’t come that far from the White Man’s Burden. The fact that I could still see it haunting the development projects of the present means it is still around.

“The White Man’s Burden” was made famous by a pro-imperialist poem of Rudyard Kipling, but it was used outside of that. The intention was to bring “civilization” (Can you think of a more ephemeral term?) to the “uncivilized.” There are many problems with this, but the biggest one, the one that is still around today, is–how do you decide at what point you are helping someone and at what point you are simply imposing your culture onto theirs?

One big reason that this is easy to do is because so many development agencies and NGO implement policies of domestic leadership from within the non-profit and do not delegate leadership roles to the people they are actually trying to help. Often, Americans come in to a “third-world country,” look around, say, “Oh we know how to fix all this. Here, we’ll do it for you.” Then after a few weeks they leave.

First, this isn’t sustainable. When the Americans build the well and don’t train anyone local on how to repair it if (read: when) it breaks or malfunctions, then they’ve done more harm than good.

Second, it creates solutions to nonexistent problems which themselves create problems. Some NGOs will put wells in places where no one would ever walk to drink from, simply because they wanted to do a good thing and never asked a local, someone who actually knows the area and what life is like there, for advice.

Third, half the time people don’t actually know what it is that they’re trying to do. People say “Let’s donate our clothes to Africa” with the same sort of half-thought that people say “I want to donate my body to science” without actually knowing what all that entails. Celebrities often begin charities to help Africa, a continent over twice the size of Europe, with a vaguely defined description that is so large it helps very few.

Fourth, it kills local trade and initiative. If you give everything away for free, it creates a culture of dependency and harms local economies, which in the long-term, hurts the communities you’re trying to help much more than it helps. And it creates a “just ask the Americans to help, they’ll do it.” A common refrain from many small children in much of sub-Saharan Africa is “Mzungu, mzungu, give me money.” [Mzungu means “white person”] The children have no filter, so they call it like they see it. Surprisingly, this seems to only be the case with international development. Ironically, many American conservatives would like to see initiatives implemented domestically that ensure people below the poverty line will not be given “handouts” but must work for what they earn. They argue for job development and growth, not relief. Yet, when scaled back to a global level, this mentality is nearly entirely reversed. Most American conservatives that I know believe strongly in donating money and belongings to poor countries, but arguing for job growth is on the back burner. It’s not that they’re against the latter. It’s merely an afterthought.

Fifth, and most importantly, it removes the dignity from the people you’re trying to help. If you go in to a completely foreign place, don’t even speak the language, and then make every decision about how to help–what does that suggest about your relationship with the people that you’re trying to help? It suggests the same thing as above–the White Man’s Burden. The idea that we are better than you because we come from a country where things are together and work okay, so we can show you how to do all of these things that you struggle with. Whether people are self-aware or not, this is the idea that many hold just beneath their breath when speaking of “Africa.” One of my least favorite things to hear (sorry if you’ve ever said this to me) is when people come back from a short-term mission trip to a third-world country and say something along the lines of “Seeing all of that just makes you realize how blessed and lucky we are here.” That statement itself implies that the speaker thinks they have it together more than those in third-world countries, whether by virtue of their own willpower or not. Not to mention the statement implies something close to poverty tourism, which necessarily places the poor into our minds as objects rather than people. And really, what would you expect if you go into a place and make every decision to “help others” without actually taking the time to ask and learn from those others? They become objects in that scenario.

Some examples:

- TOMS shoes, which everyone loves, is based on a solid idea of counter-purchases. For every pair of shoes you buy, a child in a developing country will also receive a pair. This seems like a good idea at first. You get new shoes, a child in need gets new shoes. Everybody wins, right? Well, already you’re giving away shoes, so it puts anyone who actually makes shoes in the community you’re serving out of business. Furthermore, the inability to purchase shoes is typically financial not geographical. It’s not that they can’t buy shoes because there are no shoes. They can’t buy shoes because they have no money to buy shoes. So free shoes are only a temporary solution, if they still have just as much money at the beginning as they did at the end. What happens when those shoes wear out? As they often do? Is TOMS going to go back and give them more shoes? Likely not. Even if they did, that wouldn’t be a very sustainable business practice. A better solution would be to teach a family how to make their own shoes or (even better) work with them on development goals for themselves to bring themselves out of poverty, so that they themselves can afford shoes later on. For many, wearing donated shoes actually makes things worse. People develop calluses on their feet when they have never worn shoes. Wearing shoes for six months tenderizes the calluses. Once the shoes wear out and they have to go back to being barefoot (since no company has brought them new free shoes), their feet are now tender and more susceptible to puncture and thus, infection and disease.

- Every year, the United States NFL Superbowl generates a lot of revenue in a lot of different markets. One specific way that it generates revenue is through the sale of T-shirts for the winning team. However, in order to make more money, the companies need to sell the winning T-shirts as soon as the event is over. This means that in preparation, they print multiple sets of T-shirts in advance, one with one team identified as the winner and one with the other team identified as the winner. Guess what happens to the ones for the team that eventually loses? We package them up and send them to Africa as donations. It is entirely possible for you to walk around Africa and stumble upon someone wearing a shirt reading “Atlanta Falcons, 2017 Superbowl Champions.” In many places in Africa, such as Kenya and Ghana, such donated clothes are referred to in the local language as “A white person has died.” The reason for this is because these donations are not donations so much as they are our leftovers or hand-me-downs. We give away clothes we’re finished with for free, because they’re not good enough for us, but we think they’re good enough for others (again often implying to ourselves that we are more important than those to whom we give–would you buy the clothes that you give away or are they damaged?), when instead we could be teaching people to make their own clothes and/or empowering them to have enough money to afford their own clothes. Some African countries have outright bans on imports of donated clothing because it kills local business and industry (for more on this, see Dayo Olapade’s wonderful book, The Bright Continent)

So, why all this cynicism? I know it may have seemed a little out of place. But the truth is that learning about all of these issues in college encouraged me to want to do Peace Corps even more because Peace Corps, as far as I can tell, avoids most of them (we’ll see if I’m singing a different tune by the end of my service, but thus far I don’t expect to). Of course, every agency has problems, but PC promotes a very sustainable practice that many basic NGOs fail to live up to.

Perhaps the most basic of all is simply learning the local language, which PC insists on in every country in which it is active. At the end of my first 3 months, I will have to pass a language proficiency test to be accepted as a full volunteer. I also will make the average salary of a Malawian, and live in a Malawian house. Many volunteers are not allowed to implement projects until they have spent at least 3 months in their community and in fact, PC puts us on lockdown for the first three months of our communities in order for us to integrate better. And they promote sustainability above all. We have local counterparts who we work with, so local leadership is promoted. These are all things I can support. No development model is perfect, but at this point in my life, I honestly believe that PC is doing it better than most others.

It’s 8:00 PM (I guess I should start referring to it as 20:00 from now on) and I’m sitting with my dad on the back patio of the house I grew up in. We just moved back here 2 weeks ago. It is very humid (and I know for me, even though Malawi is currently in its pseudo-winter, it’s about to get a lot more humid). It feels strange to know that I will be gone for two years. But I feel that I’m doing the right thing and I know that I’m doing what I want to do. I will miss lots of people while I’m away, and if you still don’t have my address write this down (I redacted my name for privacy reasons, though I’m not sure it matters as my name is all over this blog:

[My name], PCT

Peace Corps

PO Box 208

Lilongwe, Malawi

If you write to me, please number your letters. It’s entirely possible that one will get lost and I want to know if I’ve missed one. Also, if you send me a package, put Bible verses (or Jesus-y sounding stuff) on the outside and it will be less likely to get stolen. Also, if you send me a package, include a box of mac & cheese. If you want to talk to me at all in the next 3 months, you will have to use that address. I will have no internet whatsoever and likely no technology at all. After that my connection to the internet will be sporadic. Snail mail is ideal here. That being said, my next blog post will likely not be until September at the earliest. I plan to take a lot of notes (thanks to everyone who bought me journals) during the hiatus and copy them into the blog later. Thank you for reading; it means a lot to me and is a great way for me to process everything that’s happening and everything that I’m doing.